'Drive Your Plow Over the Bones of the Dead' book review

A brief review of a novel by the 2018 Nobel Prize for Literature winner Olga Tokarczuk

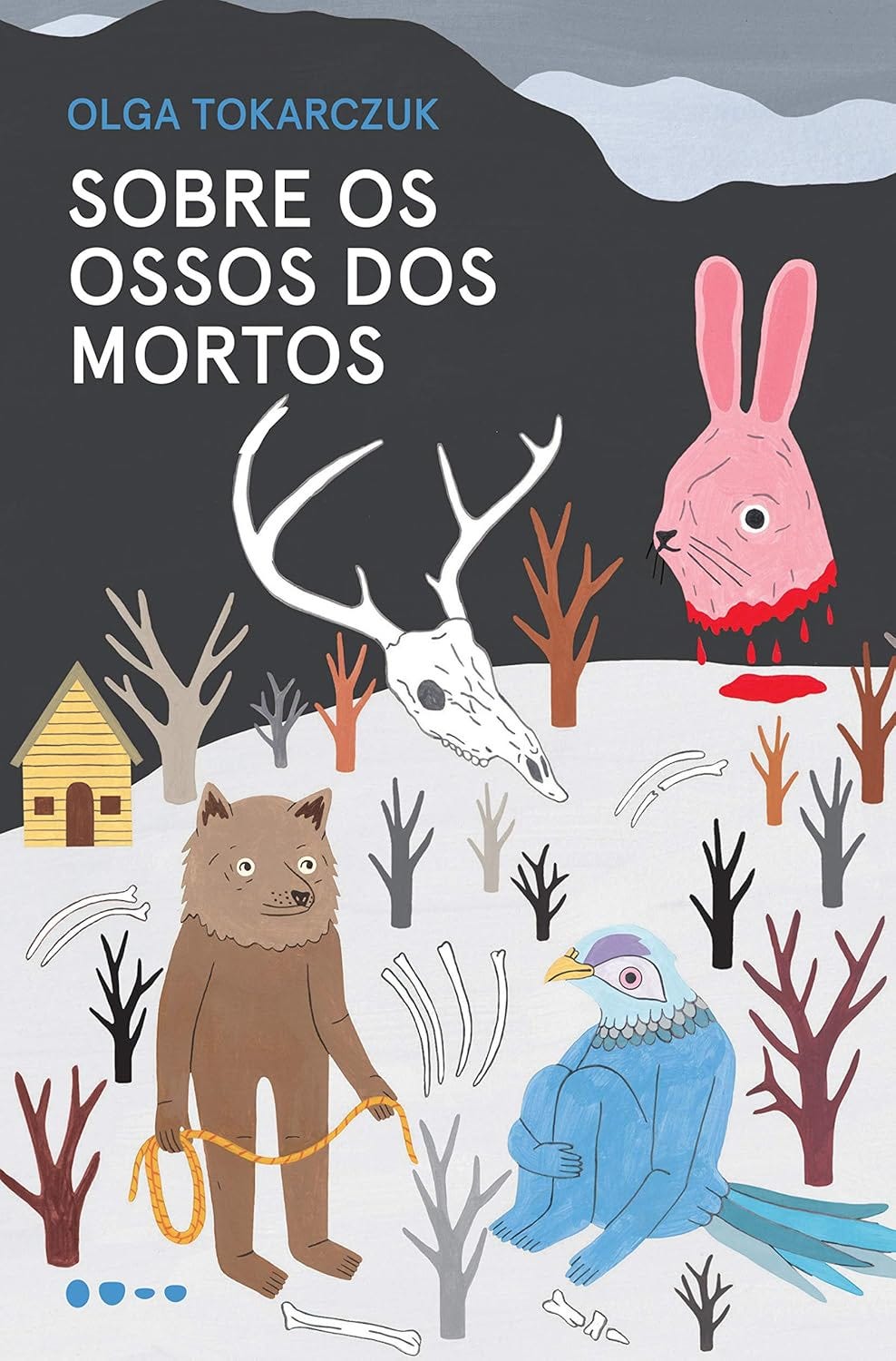

I have to admit that Drive Your Plow Over the Bones of the Dead, originally published in 2009 by polish author Olga Tokarczuk, first caught my eye because of its original and creative title and the beautiful cover art of the brazilian edition (Sobre os Ossos dos Mortos, editora Todavia). I was immediately curious about it and I googled it to know more about the plot and the author. A "Nobel Prize for Literature" title can convince almost anyone to read it, but what definitely caught me was the description about the author's style and main themes: “Olga Tokarczuk mixes thriller and humor in this reflection on the human condition and nature”. The New York Times even wrote about it as “a philosophical fable about life and death”. Done. I was convinced (even though I learned over the years not to trust The New York Times reviews or opinions on books, and you will soon know why).

At first, the narrative really caught me. I couldn't stop reading it for the first 60 pages. Even though I had started reading it on a busy day, I found time here and there to escape a little bit and read a few more pages. I gotta admit that I'm kinda easily impressed by mystery plots. Actually, I'm easily curious. If you start telling me a story or even a gossip I just gotta know how it ends. And the first scene of the book happens to be the perfect bait for curious people who just gotta know how events unfold.

It starts with a scene of death (murder? we don't know yet at this point). An old man knocks on his neighbor's door in the middle of the night — in a somewhat isolated small village, during a harsh polish winter — to tell her he found their other neighbor (also an old man) dead. He asks for her help to “straighten” the corpse before the police arrive, since the dead man was found by him in a position he considered humiliating. The neighbor who was awakened with those dreadful news, an old woman named Mrs. Dusheiko, surprisingly agrees to help and goes with him to the house of the dead man.

The reader learns really soon that the dead man, Bigfoot, was not at all a good person, a pleasant company or a respectful neighbor. He was rude, provocative and even occasionally a thief, stealing from houses of vacationers (who only lived there during the summertime). But the worst thing for the protagonist (Mrs. Dusheiko), what really struck her nerves, was his illegal practice of hunting in the local woods. Even though she concludes, at some point, that “one's life is not necessarily beneficial to others” — i.e., he had the right to live even though he was an asshole —, she ends up concluding that his death must have been a kind of punishment for his crimes against nature, for the many wild animals that he used to kill. We also learn really soon that Mrs. Dusheiko is a vegetarian, and a somewhat kind of activist for animals rights (in her own way). She is definitely very opinionated about that, and as the narrative develops, we learn that she had made several reports to the police about Bigfoot and all the illegal hunting and animal mistreatment in the past.

The first thing that started to bother me a little was the somewhat cliché aspect of the main character. She was written as a stereotypical lonely, forever-introverted, alone-in-the-woods hermit — which is not necessarily problematic in itself (even though I do think it is a bit clichéd nowadays), but I think it really depends on how the character and the narrative are developed. This could have the potential to be something as wonderful as one of Clarice Lispector's introverted and reflexive characters (like in her amazing novel Passion According to G.H.)… but it also has the potential to be something that attempts to create some depth from this reflexivity, introversion and isolation but ends up just being kind of annoying and flat. Maybe there are characters out there who are able to navigate somewhere between those two possibilities? I don't know.

Some people seem to think that the simple fact of making a character introverted and isolated will automatically make them philosophical, mysterious and deep. Don't get me wrong, I think it could be the case that a character has a sense of mystery and depth for being all reflexive, introverted and isolated. I just don't think 2+2 is 4 here. The character’s depth could be the case for Tokarczuk's protagonist if the construction of the narrative and the character’s personality, actions, reflexivity and communication worked well. But, in my view, it simply didn't, and I'll try to elaborate a little bit on why.

Let me start with her sense of being perceived by the locals as just an old woman, useless and unimportant, which could provide a good criticism (about the hegemonic society’s views on elderly people, specially on ageing women), and it could also foster an interesting plot. Although this does have a certain relevance at the end (albeit little, and even a bit forced), for the most part, she just repeats it over and over. She complains about being misunderstood, but, at the same time, she doesn't care to elaborate much so people would have more chances of actually getting to know her and understanding her — with the exception of a single friend, to whom she unsuccessfully tries to explain astrology. For the most part, she claims something, then refuses to elaborate any further, expects people to understand and agree with her, and then when they don't, she sometimes throws a fit of rage. Don't get me wrong here, I think rage is an important and complex emotion and I tend to like characters who are moved by it somehow. It makes them seem more human, less romanticized and ideal. But her reactions are just… not well-founded. She certainly has reasons of her own, but we never get to know what those are, because she simply doesn't elaborate them well. We are left with something like a simple "oh, she cares about animal life”, and that's it. I'm not saying this isn't enough reason for someone to feel anger, specially when standing before an unnecessary animal death, but I'm referring to things like... the story of her life, of her childhood, of what led her to be who she came to be, the reasons why this subject is so delicate for her... but none of that seems to matter. It seems to me that the narrative aimed for mystery and depth in this character but ended up hitting immaturity and lack of development. It's not that a character couldn't be all of those things, I think it is ok to write someone like that, superficial and a little flat. It depends on what the author wants for the story. But for me, this is fine as long as it is intentional. In this case, it seems she was written as flat while trying to be deep…Then it's just… not so good.

About her lack of effort to elaborate things so people would maybe understand her, I think she needed someone to tell her something like: “Yes, dear Mrs. Dusheiko, people don’t get you. They don’t understand you. You don’t even give them the chance to. That is precisely one of the reasons why communication is a really important aspect of social life… You know, living in society? Being part of a community? Things like that…” Of course, this doesn't mean that people will always agree. Actually, quite the contrary, I think people will always disagree, conflict will always exist, that's also part of social life. And that's actually a good thing — for me it's kinda dreadful to imagine a place where all opinions converge, all ways of thinking and perceiving the world are unified and homogeneous and nobody thinks/lives differently from one another. The point seems to lie precisely in learning how to live with the differences, and even to appreciate them (the desire for homogeneity scares me). But I'll leave it at that for now.

I think I realized that I get really bored with people who get stuck in this narrative that goes like “oh look, common people are mean and stupid, and I'm not, so I'm just gonna isolate myself here because I’m better than them and that's it”. And I think Mrs. Dusheiko would protest what I just said, because there are certain parts of the narrative in which she states that she's “not better than anyone”. But still, I get a sense that this sense of superiority underlies the narrative somehow, at least until a certain point. So, yes, I felt bored with this narrative of isolation from the “common ignorant folk”... Again, it's not like this is explicitly said by Mrs. Dusheiko, but for some reason I can't help getting this impression about her. Also, I think this book made me realize that I prefer characters with richer social lives. I prefer novels about connections, entanglements, with good communication — or at least good attempts of communicating. I.e, stories of connection instead of isolation.

Another thing about her that I found particularly bothering was the fact that she has a complete and absolute aversion to death, even though she claims to be (or at least apparently thinks of herself as) so connected to nature, to the cosmos, to the wildlife, to the “mysteries of the universe”… each of these items being essentially, intrinsically and absolutely intertwined with the natural cycles of life, which, naturally, presupposes death. Of course, one could feel connected to it all and still fear death — which is absolutely normal and human. However, I have the impression that her way of dealing with this theme wasn't just about fear, but rather an absolute aversion, abomination, as if it was somehow wrong. I get it that the sense of death being unfair is also really common and natural, mainly when someone is in a state of mourning. But her reactions to the sight of any dead animal body were just… something else.

Which leads me to the scene at the police station — for me, the worst scene in the entire book (for now it feels like all I do is criticize everything about this book, but I'm also gonna say some nice things about it, just hold on a little longer!). This scene happens after she finds a dead animal in the forest, killed by hunters. She gets really angry about it and decides, once again, to file a complaint with the police — even though she had apparently done this countless times before and it all had been for nothing. As she tries to explain to the officer that the act of hunting that particular kind of animal in that time of the year was illegal — and therefore the responsible for such an act should be investigated and accordingly punished —, she ends up being accused of exaggerating. The officer states that she cares more about animal deaths than about the mysterious human deaths that had been happening recently in the local woods. Here, she starts reaffirming what she had been saying over and over: the animals are the ones murdering humans, they are getting their revenge for years and years of violence against them. And who could blame them? I had the sense that this was a very bold claim and could build up a really interesting plot — I think so especially because I'm particularly interested in the theme of non-human agency, but we'll get back to that later — but, at this point, it develops no further.

Then, when confronted with the sense of not being understood, she starts to shout at the officers — which, in other contexts, could lead to a really cool scene —, accusing them of not caring about the lives of the wild living beings. She grabs a few bloody hairs she had picked up from the animal corpse and throws them on the officer's desk, an act to which he responds with disgust. Then, incredibly, this is what she says, and I quote (this was translated by me directly from the portuguese version):

“Are you disgusted by blood?” I asked maliciously. “But I bet you like sausage.”

This genuinely made me laugh. Because, of course… The icing on the cake. A discourse that evokes a supposed hypocrisy from people who eat meat and who, at the same time, claim to care about life — as if eating meat, feeling disgusted by blood and caring about life were things that simply cannot coexist, even in a complex and multilayered person.

“What kind of world is this? The body of a living being is transformed into shoes, meatballs, sausages, a rug next to the bed, a broth made from the bones of another being… Shoes, sofas, a bag made from the belly of a being, warming oneself with another’s skin, feeding oneself with another’s body, cutting it into pieces and frying it in oil… Is it possible that these macabre procedures really happen? This cruel, insensitive, mechanical slaughter, without any remorse, without any pause to think, although much thought is involved in ingenious philosophies and theologies. What kind of world is this where killing and causing pain is considered normal? What the hell happens to us?”

Wait, hold on a second. I mean, ok, we can see that her rage comes largely from the fact that her views on the worth of non-human life are not taken seriously, and I get that, I really do. But although she has her reasons to be mad at him — specially after he says some bullshit about her being too emotional and protective of animals because she was an old woman and maybe she had some kind of empty nest syndrome —, she seems to be mixing up two entirely different things.

Let me say this loud and clear: one thing is to call out animal mistreatment and unnecessary hunting… but what she’s doing here is something else entirely. It's like she is equating both: cruel hunters who kill and mistreat animals for fun (in this case, the men she is reporting had also killed domestic dogs) and non-vegetarian people who simply feed on meat.

And here, of course, we reach a very delicate point. Are people who eat meat indirectly responsible for animal deaths? Personally, I think so, yes. By buying meat, we create demand, which drives the market to produce more. So, yes. But while we understand that she feels frustrated because the world doesn’t work the way she thinks it should (and who doesn’t feel that way eventually, right?), there are some really important aspects of this issue that she seems to overlook — aspects that need to be taken into consideration here.

First of all, what she seems imply throughout the novel is that whoever eats meat, regardless of cultural and political context, cannot possible care about life. This kind of “vegetarianism moral” — that doesn’t at all represent the majority (I hope) of the vegetarian and/or vegan movements — shames individuals and blames them for a problem that should be addressed as a collective, structural, political, systemic one. By doing so, instead of encouraging people to engage in political struggles that address the systemic nature of this problem and thereby create chances (even if few ones) of collective change, this kind of approach reduces it to a moral aspect of a so called individual choice.

I mean, the industry of meat — responsible for terrible consequences for the planet and for the destabilization of many ecosystems— isn’t even mentioned. That doesn’t seem concern her. As long as the ‘evil hunters’ are not killing cute, innocent animals in the woods, everything seems fine. While she doesn’t need to cover every single aspect of the problem, it’s hard to ignore that she overlooks the systemic issues and instead chooses to blame it all on individuals. What seems to bother her is only the suffering of the poor non-human individuals, and not at all the ecological damage caused by large-scale meat consumption. I mean, if you wanna criticize people for eating meat, at least do it thoughtfully, right?

And here you may argue, dear reader, that she has every right to care about what she cares and she has no moral obligation whatsoever of caring about the planet. Right. But then, much of her discourse kinda falls into the very hypocrisy she just accused others of. And maybe you’re right, she has the right to care about some things and not about others. But then this makes it hard for me to like her character much. There’s just too much individual blaming, too much “good vs. evil” kind of discourse. Villains vs. heroes. And I don’t even think the protagonist of a novel necessarily needs to have a good character, be charismatic or even likeable: there are people in the world we'll disagree with, dislike, and whose views on the world will outrage us, and we can tell stories about those people too. But it seems to me that the message she’s trying to spread here is quite problematic.

I can’t help thinking about traditional hunter-gatherer communities, indigenous peoples, traditional fishing communities, small farmers who plant and raise animals for subsistence, and so on… Are they monsters too? I can’t help thinking about traditional religions in which animal sacrifices are a really important part of sacred rituals. Would they be accused of not caring about life and being hypocrites too? I’m sorry, Mrs. Dusheiko, but such a thing would be undeniably racist: no matter the approach, the Other of modernity is always put on target.

I mean, she is really utterly shocked by the act of feeding on another animal and she morally judges people for it. “(…) feeding oneself with another’s body, cutting it into pieces and frying it in oil…”. Well… yes. We do that. We feed on animals. As animals also feed on each other. It's absurd that bodies feed on other bodies? On which planet do you live, Mrs. Dusheiko? Because here on Earth, bodies do feed on other bodies. The Earth feeds us, then eventually we feed back the Earth.

Just a brief clarification: I’m absolutely not against vegetarianism or veganism. I was a vegetarian myself for 9 years. My mother is a vegetarian, other people in my family and some dear friends too. I just think people should be really careful who they point their fingers to, and in which context they do it, and with which tone they do it.

Like I said, it is totally fair to complain about unnecessary hunting, to fight for justice and against unnecessary non-human deaths. And there are so many ways to do that. But then to equate those criminals hunters to any person who simply feeds on meat? That's the thing about her blaming… She doesn't seem to point at the right target. She just shoots at everything. And then she misses it and at the same time hits a lot of different people. That's what happens when you don't specify your target correctly.

Again, I’m not at all implying that it’s ok to keep things as they are now, with the meat industry and everything. Quite the opposite. But I say once again: criticising the meat industry is not at all the same as morally blaming individuals of any context — which includes individuals in traditional communities all over the world — for eating meat. Apart from the large-scale industry, it is part of the world that animals feed on each other. May not be your choice, but it’s always been there. Would reducing our meat consumption be good for the planet? Absolutely! And that would have been a valid argument, a good motivation or justification for her anger. But no…. in her case, it's all about moral superiority. And despite her criticism of the church (in which I think she’s right), she adheres to a very similar type of moralism. This is implied in some of her speeches.

“Human beings have a great responsibility toward wild animals (…). They must live their lives with dignity, settle their accounts and record their six-month period in their karmic history — I was an animal, I lived and fed; I grazed in green fields, I gave birth to my young, I warmed them with my own body; I built nests, I fulfilled my role. When you kill them, and they die in fear and terror (…). You condemn them to hell and the whole world becomes hell. Can't people see this? Are their minds incapable of going beyond petty and selfish pleasures? The responsibility of human beings towards animals is to guide them — in successive lives — to liberation. We are all traveling in the same direction, from dependence to freedom, from ritual to free will.

“Can't people see this? Are their minds incapable of going beyond petty and selfish pleasures?” This is pretty much like saying “oh look, people are mean and stupid and I'm not, I'm better than them.” So what she does is isolate herself from society as much as she can, preventing herself from fostering and nurturing community and affective bonds as much as she can. All of this while judging everyone with her own parameters without ever trying to get to know their reasons or motivations… because she doesn't need that, right? Why complexify reality? She’s the one who is right, anyway. So self righteous. “It's me against the world”.

At the same time, according to her, we would all be traveling “in the same direction”, i.e, “from dependence to freedom”… what an evolution, right? Progress! Because animals are so dependent of their instincts and we, evolved humans, are the ones who broke free from those instincts through reason! Quickly, animals, join us! Evolve! {irony}

From ritual to free will…? Wait a second. She couldn't possibly be implying that rituals are primitive, could she? Rituals being something you move away from, evolve and progress to get rid of, only to find something more evolved: free will. Because, of course, rituals are opposed to free will, right? Rituals are irrational and typical of tribal and infantile societies, and those peoples who practice rituals — with hundreds or even thousands of years of tradition and traditional knowledge —, they're such poor people, right? So primitive! {irony}. You see my point here? This sense of superiority is disguised in layers of discourse, there's a sense a moral superiority in this "I'm the one who cares!" speech of hers. And I won’t even get started on what’s implied about animals needing humans to evolve, with humans being the heroes who could bring them to evolution…

But let me point out yet another aspect of it all. One last thing. I think her statement about animal killing being mechanical could lead to a very interesting and relevant discussion about many aspects of modernity’s mechanicism. That is, if she had mentioned the industrial processes of animal killing as being mechanical. This could lead to something close to a discussion about how we, moderns, have ontologically deprived non-human beings of any dignity or subjectivity, a process which enabled humans to treat non-humans as just passive objects without any kind of agency or personhood, thereby allowing a collective system of exploitation. But, again, nope, not even close to anything like it. She just points to any hunting as “mechanical”, just throws the word there. Even though it made sense to call it mechanical in the context of the hunters portrayed in the novel, she says it in a way that implies that any hunting practice would be mechanical. And that, in my view, is absolutely not always the case — I’m thinking of traditional/animist/ indigenous communities here.

Well… at the end, the thing I thought was cool (and really at this point was what kept me going) was the non-human agency implied in her allegation that animals were intentionally committing all those murders to get revenge. And honestly, what an interesting and original plot it would have been if animals were doing so! But no, later on, we learn who really committed them: it was a human, and the motivations were rather… not well justified.

I have another thing or two to complain about Mrs. Dusheiko, but I’ll try to keep it short now. This is again about her lack of ability to communicate: she mentions two past lovers, and she emphasizes that one of them was a protestant and the other was a catholic. This could have been a good opportunity for us to get to know her a bit more, to know about her past, her story, maybe to build a stronger bond with her, to connect to the character in a more emotional way… But no. She refuses to elaborate further on anything emotional or anything that would give her character a little more depth. It’s like she’s building a wall between herself and the reader — so, it’s not the reader’s fault if they end up not sympathizing with her much, huh?

About her catholic lover, she only tells us that “it didn’t end up well”. What about some development? Interesting details that would help us to get to know her better? Nope. About the protestant lover, she cares to elaborate a little bit more, but just enough to let us know that he had a particular view on human suffering (which, in the end of the day, is not so exclusive to him): “the one who suffers is healthy!” (!!!), the one who suffers is dignified (!!!). In my experience, this is a typical protestant view. Dignity through suffering. Purpose and purification through suffering. And then, she goes on to say that she agrees with him, which made me remember a quote by Max Frisch:

Jeder Mensch erfindet sich früher oder später eine Geschichte, die er für sein Leben hält…

This translates to something along the lines of: “sooner or later, each person finds themselves a story, which then they hold as their life”. As I mentioned earlier, one thing that bothered me about this character since the very beginning was what I now call “the cliché of the suffering hermit”. Everything is pain, everything is sadness, everything is a burden. In Mrs. Dusheiko’s case, it seems clear to me that this is something she is choosing — and I’m being careful to say this, because I think that stating that someone is “simply choosing to see suffering everywhere” can be, depending on the context, a very cruel thing to say. And of course, even if she does choose it, she is free to do so. But thanks to this book, I came to realize that the “suffering hermit” is not my favorite type of character. In the context of this novel, I don’t think this aspect adds much (or at least, not much good), and it even reinforces an outdated sense of dignity (and sometimes even superiority, even though the character would definitely deny it), and also a sense of isolation and individuality that is so tiresome even to argue about… and even makes it more difficult to build community bonds — which is something I think we should reinforce in our narratives for the present and for the future. As I said, I think we need stories of connection instead of isolation.

Well… and now, dear reader, after all this criticism, I’m finally gonna say something nice about this book! Thanks for holding on for so long.

Closer to the end, there is a fairly well-placed criticism of the church’s teachings regarding their views on the so called human superiority over animals. She points out biblical passages and also some aspects of the priest’s speech that explicitly aim to give a sort of divine right to humans so they can subdue and exploit non-humans and the Earth. Humans, those made in the image and likeness of God, those endowed with rationality, so different from the irrational beasts with no agency, subjectivity or dignity… Humans would then be the rulers of the world. She identifies it clearly and rebels against it.

Regarding the narrative rhythm, I think it oscillates a bit. There are chapters where things happen very quickly, and then chapters in which things are slow and not much happens. At first, this felt a bit odd to me. But looking back now, this might be one of the positive aspects of the book for me. I think I’ll choose to interpret these rhythm changes as a reflection of life’s rhythm itself: sometimes, for really long stretches of our lives, nothing particularly important happens, and then, somehow, out of nowhere, events begin to unfold one after another. I finished the book feeling that the fast chapters compensate for the slow ones (and vice-versa), resulting in a fairly good overall rhythm.

From here on, this review will contain spoilers. Consider yourself warned!

I have two main comments about the fact that Mrs. Dusheiko was committing all the murders herself (except, apparently, for Bigfoot, who really seems to have choked to death on his own): the first one concerns the credibility of the narrator. The fact that she made us readers believe her innocence builds a nice narration strategy. An unreliable narrator… This isn’t exactly new, but I like it. You end up feeling deceived, just like the people around her. Maybe I’m a fool, but I believed in her innocence until the last second, until she confessed, despite the previous evidence suggesting she might have been responsible for the murders… Maybe the fact that she was the one murdering humans can be interpreted as giving her character an “anti-hero” aspect, or something like that. It seems like this is a strong trend in contemporary novels — I mean, writing from the perspective of an anti-hero, and not the same old hero plots over and over again —, and I like it.

The second comment concerns the frustrated expectation of the non-human agency implied by her statement that they were the ones murdering people. I find it really frustrating that this book had so much potential in terms of its plot. This book could have sparked an interesting discussion about non-human agency, the ways we interpret non-human actions, and how we perceive them ontologically. But in the end, she was just a moralizing vegetarian who murdered hunters and blamed it on animals. “They get their revenge through me”. In the end, it’s just another crime novel.

As usual, the New York Times disappoints me in every single overly positive review they write. Maybe I’m just too demanding when it comes to literary standards? Or maybe our tastes simply don’t align. But honestly, judging by this book, I can't see a reason for a Nobel Prize. I mean, it passes the time, sure, and it includes one or two well-placed criticisms, but that’s it for me.